What (Who, How) I Am and Why I Write

I've rejected the generic title that has the relative pronoun who as its starting point for one simple, powerful reason. I have no answer to the question – and this I confess with some embarrassment – though I've been asking it again and again for no less than seventy years and have never come up with anything plausible in response. I can't say, then, who I am but what I am and, even then, only approximately. If I'd had to answer the question when I was a cartoonist I would have used a sketch, in the style of the ones Leonardo da Vinci did and maybe even the accompanying explanations would have needed to be read with a mirror. Imagine the contrivance I use as a self-portrait. It's a big copper funnel that must be thirty centimetres across the mouth. The whole thing, from the top to the extreme end of the cone, must measure about the same. The entire structure plugs into a glass flask, discretely medium-sized, transparent and slightly tinted with phthalocyanine green. Now you can see why I write but just let me conclude the matter of the funnel likeness. It's the receptacle of my self-education. Over eighty years I've been pouring into it an awesome heap of trifles. You've seen that the mouth is wide but the bottom end of the funnel is very narrow and, accordingly, things drop down into the flask very laboriously. [...] Eighty years devoted to clogging a funnel with very compact things which hurt as they passed through a duct that implacably squeezed them. Finally they ended up in the bottle, the flask tinged green with a touch of phthalocyanine. Things have dropped slowly down into the lower receptacle. The glassy nature of the flask gives them an elongated optical shape. Why I write. I do it to relate the impressions of this whole elongated muddle, the things piled up in my eighty-one-year-old glass flask. Everything's there, then – wars and boxers, actors and construction bosses, surveyors and other poets, violinists and schoolteachers, emperors and wall-paperers, aviators like Louis Blériot and cosmonauts like Armstrong, et cetera, and they've nourished my life and instilled in me a mad desire to share it with someone. May no one be surprised by my chaotic way of going about things, good-for-nothing by nature as I am, or by my having my way with a string of ill-digested facts. With this, I justify the fact that in my books I've striven to explain in detail everything I've seen inside the flask, through this perception of mine, scant and adulterated, slightly tinged with green, which is apt since it is the colour of hope.

"Què (qui, com) sóc i per què escric" (What (Who, How) I Am and Why I Write), in L'Escriptor del mes (Writer of the Month). Barcelona: Institució de les Lletres Catalanes, 1992.

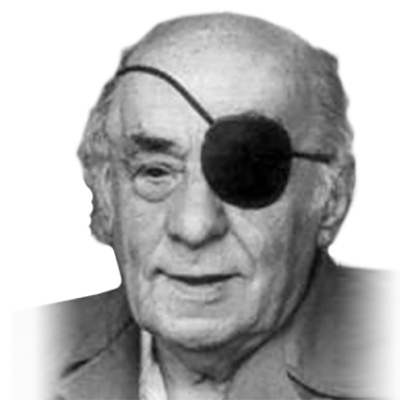

Avel·lí Artís-Gener, Tísner

(Nou diccionari 62 de la literatura catalana – New Dictionary 62 of Catalan Literature)

Barcelona, 1912-2000. Fiction writer, journalist, puppeteer, set designer and painter. He trained as a set designer and cartoonist and very soon became interested in journalism. He worked as an editor in the weekly Bandera and with newspapers like L'Opinió, La Rambla and La publicitat, frequently using the name of Tísner. He signed his satirical caricatures in L'Esquella de la Torratxa, La Campana de Gràcia and El Be Negre with the same pseudonym. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, he enlisted as a volunteer in the Republican Army. When the war ended he was imprisoned in France, after which he emigrated with his family to Mexico, where he was to live for twenty-six years during which time he worked as a cartoonist, publicist, painter and set designer. Meanwhile, his newspaper articles and other activities were staunchly committed to informing the public about Catalan culture. He returned to Barcelona in 1965 and very soon began to participate in cultural and political life. As a journalist and cartoonist he worked for Tele-Exprés, Tele-Estel, El Noticiero, and Avui. He also took part in the campaigns for standardisation of the Catalan language, in congresses and in Catalan language associations. He wrote books for children and young people and worked as a translator. In recognition of his work he was awarded the Jaume I Prize (1986) and the Premi d'Honor de les Lletres Catalanes (Catalan Letters Prize of Honour, 1997), among others.

His literary production is wide-ranging and notable for his constant quest for new forms and techniques. His first book 556 Brigada Mixta (556 Mixed Brigade, Mexico, 1945) is a fictionalised account of the Civil War in the words of an anonymous soldier who describes daily life on the front. The value of the work resides in the author's being able to offer, just after the war, a de-dramatised story of the conflict, thanks to irony and touches of humour. He moves from the eyewitness account to fiction with Les dues funcions del circ (The Two Functions of Circus, 1966), his tale of the experiences of two brothers who, by chance, end up in Martinique. This is a recurrent theme in the literature of exile: the devouring power of the tropics which annihilates the individual, and the clash of two cultures. The storytelling technique, however, is innovative since it offers different levels of narrative and perspective revealing the relativeness of life, making fiction indistinguishable from reality. The complex structure is enhanced by objectivist techniques and the use of vivid, fast-paced language. The second novel is Paraules d'Opòton el Vell (Words of the Old man Opòton, 1968), which uses ironic subversion of the historical chronicle of the "conquest" to give a relativist account and a critique of imperialism. His book Prohibida l'evasió (Evasion Prohibited, 1969) heads in another direction. This is a philosophical novel, clearly influenced by existentialism and the nouveau roman and is, as the author himself says, his song against non-communication. Here, he uses cinematographic techniques to describe the lives of some young Europeans in a degrading reality from which they cannot escape because there is a camera, the collective conscience, monitoring them. If this has been seen as one of his deepest, most cosmopolitan works, his most politically committed book is L'Enquesta del Canal 4 (1973), in which one clearly sees opposition to and criticism of the Franco regime. This is a political allegory based on his creation of a microcosm that represents society: a hierarchically-organised television channel that regulates and controls everything. His arguments are conveyed in very rich language and in a complex structure that requires a reader capable of reconstructing a text replete with elisions and calligrammatic wordplay. Some years later, he published the novel Els gossos d'Acteó (Actaeon's Dogs, 1983), a critique of an old, corrupt society moved by lust for money and that can only be saved by the young people. The last major work is comprised by the four volumes of his memoirs, Viure i veure (To Live and to See) in which Tísner analyses his life and the period of history in which he lived, with particular emphasis on the Civil War. Like the rest of his work, this is a significant literary contribution and an insider's account of Catalan literature and society.

Copyright text © 2000 Edicions 62