The Towpath That Cannot be Walked

Simona Škrabec

Honorat from the Cafè anxiously studies the surface of the river through a magnificent telescope as he waits in vain for the Carlota to arrive. The boat, with the old riverman Arquímedes Quintana at the helm, heaves into the visual field of telescope seven days later. Then, the anonymous chronicler—through whose eyes the whole story is told—notes how intently the chemist observes the boat “surging through the muddy waters”.

Jesús Moncada’s novel is composed of similar scenes reviving the memories of more than two hundred characters. The story cannot be read as if it had a single narrative thread. Moncada offers a text which, in a nutshell, might be described as the chronicle of a town, covering events from the mid-nineteenth century through to the 1960s. Nevertheless, the presence of the historical past is nothing more than the rumbling of distant guns. What lies hidden, then, behind the joyful gambolling of the boat as she cuts through the current on her way upstream?

With scenes like the homecoming of the Carlota, Jesús Moncada creates a sort of secret dialogue with the reader. These clear images, as precise as if they had been photographed, make the text rather more than a faithful description of the beating heart of a town submerged under the water.

The faces will change but the world turning around on its own axis will always remain the same. The thread is always the same thread, although sometimes it rolls up and then unrolls. This image is so different from that of the mythical Fates spinning their silken thread, their golden thread, the thread of life, until it snaps. With the old stories, a person can have the sensation that, out of a tangle of carded wool, there emerges the thread of a unique life that goes off in a single direction. Moncada, however, sets his characters in a different world, one that is predestined and closed in on itself. Mequinensa is faced with a crucial, eternally irremediable fact. The die is cast and it must literally disappear from the face of the earth.

Riverboats transport everything that has been part of this community’s life. Houses also conceal objects that belong to a shared history, so the novel constructs the town’s life with countless shards of a broken mirror. Where is the sum of all the events of the past? The overwhelming impression is that there are too many pieces to put together into a single, coherent whole.

At first it seems that the lost Mequinensa represents a self-sufficient world, a mythical universe governed by cyclical time, the world of the epic. Moncada’s novel does not imitate anything and neither is it an imperfect copy of some blissful ideal. His pen shuns imitation and simply puts together the pieces of a mosaic. And it is not possible to bring the bits together into a living organism. This novel is the story of the pain caused by the loss of a beloved world and, if this pain can be emphasised in any way, it would be by showing that there is no master craftsman anywhere in the world with the skills to piece together into a flawless mirror all the fragments that are lying scattered on the ground.

Narrating the past is as delicate as painting a fresco for it, too, is subject to the laws of physical decay. At the end of the day, books are only objects and their paper will also turn into dust one day just like the boats rotting at the Mequinensa quays. The story is a mask and behind it there yawns a horrific abyss.

This is a novel about memory, about the fact that life slips through fingers like fine beach sand and nothing can hold it back. The human being is a creature woven from time. But the past is inaccessible. There is nothing we can do to restore to our lives the happiness that we might have felt just a moment ago. Nothing can bring back to us the trusting gaze of the infant who sees the world as a safe and beautiful place. No, there is no need to construct a dam next to the town where we were born so that the river will overflow its banks and flood the places that taught us how to live. The river of time will bear them off in any case.

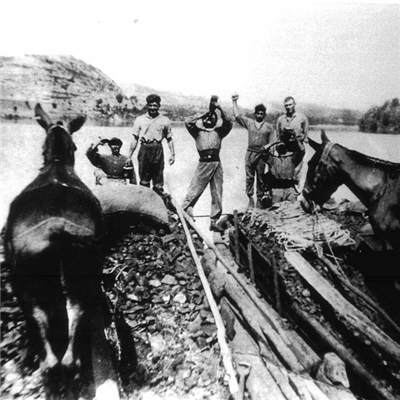

A pitiless flood will sweep away everything that was once ours. This happens every day, every moment, and to every one of us. Jesús Moncada is the boatman who goes down to the riverbank and, with the aid of a thick rope tied to the top of a tree, drags behind him the boat of his life. It carries a heavy cargo, this boat, for the burden of memory he tows is by no means light. Yet Moncada doggedly plods along the towpath and, in the end, like the mule Trèvol, reaches the town which, though it might not be found on any map, still exists in memory.

This is the impression the novel’s title gives, summing up its contents in a singular way and yet, at the same time, it is possible to find in this facet of the book what the story means for so many faithful readers around the world. Everybody, from Catalonia to Japan, from Sweden to Romania, today and in 1988—when the novel was first published—understands that time is a fast-flowing river which knows only one direction, and that life flows towards death.

Fragment of an essay by Simona Škrabec, “Camí de sirga que no es pot recórrer a peu” (The Towpath That Cannot be Walked), Els Marges, 76 (Spring 2005). Reproduced in Visat, 1 (January 2006).