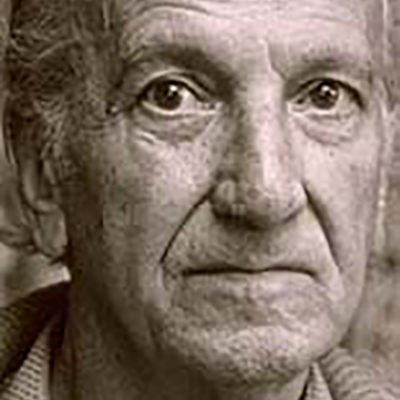

Xavier Benguerel

Neus Real (Autonomous University of Barcelona)

From the standpoint of literary history, Xavier Benguerel is a writer who has a lot to offer. A member of the same generation as Anna Murià, Francesc Trabal, Maria Teresa Vernet, Ernest Martínez Ferrando, Mercè Rodoreda, Pere Calders, et cetera, his life story and his literary production are two strands through which, whether they are entwined or separate, one can follow the processes of twentieth-century Catalan culture. Convinced that it is craft that makes the writer, Benguerel constantly reworked and rewrote his books with the result that he offers first-rate information for analysing and understanding nothing less than seven decades of writing. These are seven decades in which one should always bear in mind the range of literary-cultural endeavours in which he participated and all the documentation he left on this (no bagatelle).

These initiatives, these traces left by a witness, the written fruits of Benguerel's relationships and the numerous titles that make up the corpus of his work, have given shape to a rich and plural whole that offers, needless to say, many possibilities for approximation by the researcher. This set of works, as is well-known, includes all the genres (although, here, we are speaking essentially of a narrator): from poetry, to literary criticism, to the short story, the novel, theatre, memoirs, essay, journalism and translations (of such illustrious names as Baudelaire, Poe, Salinger and Valéry, among many others). Then again, are his endeavours in the institutional and publishing spheres (for example the review Germanor, in Chile; the Club dels Novel·listes (Novelists' Club) after January 1936, his work for the Institució de les Lletres Catalanes (Institute of Catalan Letters) during the Civil War, and with the collections "El Pi de les Tres Branques", from exile, and "El Club dels Novel·listes", on his return to Barcelona). It is in relation with all this that we also find a prodigious quantity of letters exchanged with an extremely long list of intellectuals including Josep Carner, Salvador Espriu, Josep Ferrater Mora, J.V. Foix, Domènec Guansé, Joan Oliver, Joan Puig i Ferreter, Joan Sales and Joan Triadú (and these letters have been read and studied and, in some cases, classified and published by Lluís Busquets i Grabulosa, a specialist in Benguerel and whose book Xavier Benguerel, la màscara i el mirall [Xavier Benguerel: the Mask and the Mirror] is essential reading).

As for his literature in the 1920s and 1930s, Xavier Benguerel presents an ever-expanding character along with some simultaneous particularities that bestow on him a well-defined personality right at the start of his writing career. Pàgines d'un adolescent [Pages of an Adolescent] (1930), for which he obtained the "Les Ales Esteses" Collection Prize in 1929, reveals some significant traits in this regard: the importance of narrative in Benguerel's writing, his recurrent resort to autobiographical material, the central space occupied by the neighbourhood Poble Nou and, finally, a style and a way of working that make his texts stand out in every period even while he is always responding to the context and fitting in with the literary trends of the day. Hence, through the story of Ricard, the young Benguerel made his debut with a novel that ascribed to the psychologically-grounded and Barcelona-centred themes of the time, choosing as his preferential motif one that fitted into the twofold framework that shaped the literary concerns of sexuality and the unconscious, on the one hand, and the cultural volition of creating standards and modernising literature (and, on the rebound, society) in Catalonia, on the other. At the same time, he put all this through the filter of his own experience, shaping it with a lyricism born of another of his qualities, that of a poet, while also manifesting very specific cultural inquietudes that remained with him to the end of his days, and that would gradually acquire increasing prominence in his work.

La vida d'Olga [The Life of Olga] (1934) and El teu secret [Your Secret] (1935) represent continuity with his first title, even while acommodating the new concerns imposed by the epoch. These two novels retain their basic psychological interest and urban settings, particularly emphasising sexual matters (understood in the broadest sense). The former work was primarily devoted to the problem of lack of communication in love, and Benguerel specified his theme in the conjugal difficulties of Octavi and Olga, two characters on the basis of whom he raised the issues of matrimonial and extra-matrimonial ties, with sexuality and the family as his background, at a time of incipient but significant change in gender relations (the social construction of sex). These changes, among many other factors, were determinant as a stimulus for literature that was able to attract female readers (essentially, literature dealing with questions that interested women). The latter book, El teu secret, focused on an adolescent's discovery of the world, embodying this in a young man from Poble Nou, once again named Ricard, but much more riskily in dealing with incest (a burning issue in the world of letters at the time). This work directly linked up with Pàgines d'un adolescent and was a clear harbinger of Suburbi [Suburb] (1936), a work that was awarded the Premi dels Novel·listes (Novelists' Prize), and in which the social dimension was to play a more prominent role.

These early novels, which were so bound to the pre-war setting (to its leading tendencies, its demands and its needs), already contain the germ of what was to be Benguerel's hallmark and that, one way or another, throws light both on his works and on what makes of him an interesting, modern writer throughout the twentieth century while also endowing his fiction with relevance even today at the start of the 21st century. I refer to the question of identity. Benguerel's work raises the question of the identity of contemporary man from several perspectives that range from adolescent insecurity, through to adult uncertainty, moving through many states of reflection and materialisation without ever reaching any definitive conclusion (and, in this regard, it is no accident that Benguerel's last novel should be titled I tu qui ets? [And You, Who Are You?] and that it should tell the story of Valentí, another young worker from Poble Nou who has to confront a future that is quite difficult, from a past and a present that are determined by the social reality of his neighbourhood in the pre-war period, without knowing very well who he is or how to live beyond mere reaction to the events that keep happening). Pain, doubts, false appearances, destructive impulses, sin, guilt, disenchantment, incomprehension, the dark parts of the soul, resignation, poverty but also love, comradeship, faith, goodness, hope and light... the inner facets (complexity) of the being are shown through characters who tend to be born, to grow and to die as best they can rather than as they want. And all these facets drift, one way or another, into estrangement. In Benguerel's works, even in the 1930s, the "I" is always at least one other.

In this quest of making sense of world in which it seems there is no sense - not, at least, from the perspective of true human dignity and solidarity - Benguerel thrusts deeply into all the paths that open up before him at every stage. In his hands, the crisis of adolescence, the first adult drama, love, sex, the social reality of Poble Nou in the early decades of the twentieth century, collective history (Tragic Week, pistolerismo (the gun-law days of the early twenties), the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, war, exile...) and any other material apt for literary creation generate a spiral around the nucleus of which are the same basic and essential questions: who we really are and what the sense of our existence might be. In seeking answers, or at least some keys to these questions, Benguerel constructs his narrative corpus on the foundations of direct or indirect experiences and a range of literary possibilities. If, before the Civil War, he re-created a perfectly recognisable Barcelona setting under the aegis of the fictional demands of the times, in the post-war period he linked up with a certain Catholic point of view, as well as with existentialism in order to continue probing the same theme from the domain of imaginative fiction -especially with El testament [The Will] (1955), El viatge [The Journey] (1957) and L'intrús [The Intruder] (1960)- and from his novelised account of the defeat of 1939, the republican exodus (in particular the life of the refugees in the French concentration camps) and the reprisals of the Franco regime against those who remained in exile or returned, with Els fugitius [The Fugitives] (1956), which was reworked and expanded to become Els vençuts [The Vanquished] (1969).

Without denying the merits of his short stories or his other novels (or the rest of his literature), perhaps it might be said that Els vençuts (a work coinciding with the peak of his creative maturity) symbolises better than any other title Xavier Benguerel's contribution and his way of working. This volume, which was re-worked in the 1960s on the basis of an original text from the 1950s and revised again in 1970 and 1972, is of an extremely high literary quality and unquestionable cultural significance and, moreover, it makes the intellectual position of its author perfectly clear. He himself explains his motivations in a presentation that, with seamless honesty, goes back to his sense of responsibility and commitment to which I referred above: "in our literature we lacked documents about what were probably the most impressive chapters of our contemporary history and [...] I, for the simple fact of having been part of it and witness to it, was called upon to publish them, even if it had to be so many years later" because "the origins of these episodes constitute the quintessence of the history that we are still living today and that we continue to drag along with us".

Neus Real, text produced for the function in honour of Xavier Benguerel, organised by the Institució de les Lletres Catalanes on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his birth (14 December 2005).

Copyright text © 2005 Neus Real

They Have Said...

Benguerel has been, from the very start, a long-distance, thoroughbred writer. He has written [...] in hundreds, in thousands of pages, unhurried stories of difficult spirits, complex dramas of men and families, human lives and deaths. [...] Benguerel wrote always and despite everything [...].Nobody can deny that, for a writer in the Catalan language and with the special hazards of his times, Xavier Benguerel reveals at the very least a rigorous, serene and unshakable fidelity to the destiny he freely accepted. Yet this is by no means the end of it. Benguerel is a storyteller of sustained creative thrust and a stylist all at once. He brings together power and quality, aspiring to marry the finesse of the silversmith to the grandiosity of monumental architecture. He loves the language from its purest roots and knows that the real writer is an eternal apprentice of the trade who needs to hone the tools of his craft a little more every day and to keep enhancing the quality of his work.

Joan Oliver, Prologue to El desaparegut [The Disappeared] (Barcelona, Selecta, 1955).

We can pigeonhole Benguerel's novels under several headings.

First of all, the personal world, the awakening into adult life, concern him. From his first book, Pàgines d'un adolescent, we understand that man is capable of corrupting love - and hence he loads his sense of guilt with responsibility. However, love also opens him up to others, which is to say to the opposite and complementary sex, with all the problems involved, at times requiring heroism (El teu secret), at other times discovering disillusion (La veritat del foc [The Truth of Fire]) but also, in the broader scheme of things, to his own neighbourhood community as well (in Suburbi, where the two main characters feel "guilty forevermore2 after an abortion, although the male character will be able to steer clear of the vengeful anarchist law-of-the-gun even though he has participated in other clandestine activities). It might be said that, as he becomes more adult, Benguerel confronts reality in a way that is proportional to the maturity of his reflections. Let us not forget, he was the adolescent who, playing at literature, wrote La família Rouquier [The Rouquier Family] yet, in this novel, life and love are treated with the same nuances that his adult capacities offer; shy people, too, can burn with love or be -and again man takes on his load of guilt- killers (La màscara [The Mask] and L'home dins el mirall [The Man in the Mirror]); beyond rancour over a wife's infidelity there can be faithful love (El testament); beyond human love, there is an obscure divine or diabolical calling (El viatge and L'intrús); beyond love-disappointment there is sacrifice (La vida d'Olga and El pobre senyor Font [Poor Mr. Font]).

However, this journey through his opus -perhaps too intimate or personal- has not yet opened up into Benguerel's yearning for sincerity or his powers of reflection and, in the next step, he widens the circle: he needs a kind of reflection that will embrace his own story within the story of his community. He needs to extract a lesson from the vicissitudes it has been his lot to live with the defeat of the war. The placidity of the early thirties, with a bourgeoisie that seemed to have got the upper hand after the conflictive twenties (Gorra de plat [Policeman's Cap]), soon hurls him into a war (1939), flight from the country of the routed (Els vençuts) and an exile that is never-ending, even with repatriation (El llibre del retorn [The Book of return]). The chronicle is complete; the frieze drawn. Readers and critics have found his work to be a compassionate affidavit to the injustice his people have suffered.

Nevertheless, Benguerel is still not satisfied. He has to go further, to analyse the circumstances that made the collapse possible, to go back to his neighbourhood, to the clandestine struggles of his youth. With Icària, Icària.... [Ikaria, Ikaria...] he will see it through to the end. Utopias, like the youthful anarchist struggles of his neighbourhood, only benefit the powerful. If this work is more searing than any other, it is because we already know the end of the ending: we know that the ideals of those who fought in the streets against the Franco uprising are going to end up defeated, in exile, and that they will destroy lives and loves (Appassionata). Perhaps they weren't worth it. Now the insignificance of those lives, the abdication in the face of destiny, seem evident. In I tu, qui ets?, we have seen it. The reflection is over. Nothing is sure except one's own insignificance. The humility of silence is imposed.

Lluís Busquets i Grabulosa, Xavier Benguerel. La màscara i el mirall (Barcelona, PAM, 1995).