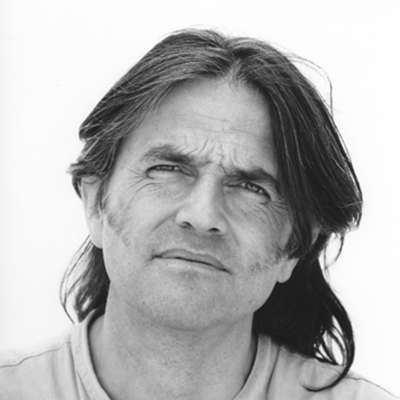

Perejaume

Toni Sala

Sant Pol de Mar, 1957. Artist and poet

Benet Martorell was the first person to put a paintbrush between Perejaume’s fingers. At the end of his life, Martorell talked about nothing else but the painter Raurich. Perejaume was infatuated with old Martorell just as old Martorell had been with the painter Raurich.

In Nocturn, Perejaume wrote about the paintings in Martorell’s house. "As far as I possibly could, I tried in my apprenticeship to capture the rare light of those works in which the glass seemed to close over a primordial, transcendent world."

His father had been a farmer. He has friends who are too. Perejaume, perfectly attuned to the comedy of those Maresme farmers, can do affectionate imitations of human candour, tender imitations, in approximation and self-indulgence, of characters he is close to. Without any need to use inverted commas, Perejaume smoothes off the edges with intellectual, loving refinement and turns into a farmer, in the still-close ancestrality of all our forebears, turning in on himself, and it seems we have known him all our lives.

The first oils Perejaume painted, towards the end of the 1970s and early 1980s, were landscapes of Montnegre, behind Sant Pol de Mar, twilight or nocturnal mountains, lilac-hued, magical. They are the embryo of all that was to come later.

Then they were newly-accomplished landscapes and today their paint is still fresh. These early oil paintings were exhibited not long ago at the Palau de Caldetes Foundation. They are works painted when Perejaume was twenty, with all the novelty of the political and personal conjuncture, paintings composed during the summers he spent at the Riera de Fuirosos house or at the Oller de la Cortada house, in the Montnegre heartland.

While he was studying history of art, Perejaume took part in the strikes and demonstrations of the time. He went to the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc to sketch models and draw. It was there that he had his first exhibition. When Joan Brossa saw those paintings, he was astounded.

Perejaume used to visit Brossa in his studio in the Balmes/Travessera part of town. Brossa was a categorical individual with a perfectly constructed Olympus.

"So", Brossa used to say when they got together, "Do you still like Marià Manent?

"Yes I do!"

"But how can that be? What are you saying? How can you like Marià Manent! What’s this you’re telling me, Perejaume! What are you saying!"

Brossa is a constant reference in Perejaume’s painting and poetry. The other presence scattered throughout his work is that of Josep Vicenç Foix. The latter had received him in the dining room of his home. He had a library there, behind a curtain, a small, full library with all the books neatly ordered. Foix reached for a volume and opened it. He recited to his disciple. Perejaume was fascinated. He saw that the volume had an ex libris stuck to the back. On it was a map of the library on which was marked the precise spot the volume occupied. And the young Perejaume, who was barely able to keep his room tidy, went back home in despair, with his artistic idée fixe mortally wounded. How could he, who didn’t know a single thing, ever do anything good!

For all his admiration, Perejaume was never afraid to follow too closely what Foix and Brossa were doing in their works. On the contrary. His fear was that he wouldn’t be up to them or even come near them.

"At that time Foix and Brossa were essential. I have to be doubly grateful to them because they helped me, guided me right at the point when the cabbage was opening up and that’s when you need mentors. I wouldn’t be anything of what I am now if they or Bartomeu Rosselló-Pòrcel or Manent hadn’t written. Especially the more territorial writers, the ones that described landscape... My education was with those people. Or if Mir hadn’t painted, because I was fanatical about the Joaquim Mir of Mallorca, the early Mir. In those days, it was a Mir, a James Ensor, a Ferdinand Hodler … Oh, I used to make pilgrimages to go and see a Mir!

After the refinement and soaking up of reality that had been attained even among the pictorial avant-garde and, in particular, after the cool-headedness and intellectualisation that predominated therein, bringing about a split between the painting of connoisseurs and dealers and painting for consumption, how can we recover physicality, this material absorption that the senses demand of all the arts? Matter painting came back to the real world, starting out from the inevitable and immediate truth constituted by the materials themselves: the brushstroke, the canvas, the frame of the painting.

If reality was dead when it came to the painting after being so loaded down with the history of art perhaps, as if it were an injured person, we should ask it not to move. We’ll go there ourselves.

In the paintings, in the actions, in the vocabulary of Perejaume’s poetry, the capturing is important. Perejaume constructs enormous frames that adapt to the orography, the geology of his mountains, as if they were rubber. He takes them there, sets them down and the undulating frame captures the peak. Or he hammers four enormous stainless steel drawing pins into the sand on the beach, one on each corner of the landscape he wants to retain, so it won’t move. He paints the Claude Monet work with the painter setting a cobweb on the Vila-Roja pass, or he adds the gilded frames of the Liceu proscenium, drawn in to pass like flying saucers over the Pyrenean landscape of Costuix: frames that are like golden falcons, somewhat sinister, about to fall on the prey, which is reality. Or like the Sant Pol fisherman, he makes nets of frames.

He forges in steel the word "lied" to half-submerge it later in the river so that the water goes through the middle of the loop of the l, through the mouth of the e, and through the little conduit of the d and, lo and behold, the water interprets this lied.

Perejaume corrects the streambed in Folgueroles, writing in water the form Verdaguer. He makes the pebbles speak as they drop off a slope, filming them as they come unstuck and roll, subtitling the sound they make, what they say. Perejaume lets the wind-stirred holm-oaks speak...

He is the farmer Verdaguer, filtered through Foix at his most visionary and perhaps the swansong of the agrarian in our literature. Once one has read and re-read this highly original volume, one sees clearly that these radiantly imaginative and vitalist poems were forming themselves over years and years of Montnegre. That they were oozing out, that they continue to do so, fashioning themselves.

In Obreda, nature and people, the "geo-human reality" is giving shape to itself and the marvellous thing is that it does so without voluntary intervention, in pure mimesis of itself because, for absolute mimesis, the absolute disappearance of the intermediary would be required.

"I see a line of Ovid on the contours of the Corredor range", he says and this leads me to recall a verse of Metamorphoses. Metamorphoses would have been a good title for this collection of poems too. I’m thinking about when Ovid recounts the myth of Pygmalion. Pygmalion sculpted the figure of a maiden that was so utterly real, of such absolute mimesis that, Ovid says, if the sculpture stayed still it wasn’t because it couldn’t move but, on the contrary, it was out of modesty. He then writes, "...you see how art hides its art", by which he means that the mimesis is so complete that the artifice, the sculptor is nowhere to be seen.

A pure creator has no choice but to remain hidden, like God.

Toni Sala, Comelade, Casassas, Perejaume (Barcelona, Edicions 62, 2006)

Copyright text © 2008 Toni Sala