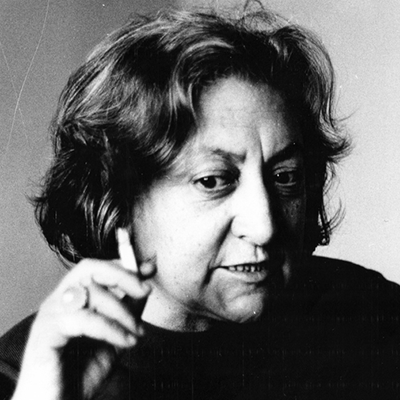

Maria Aurèlia Capmany

Montserrat Palau

Educated in some years of "normality" and imbued with republican ideas, Maria Aurèlia Capmany (Barcelona, 1918-1991) did not have an easy time becoming a writer in the Catalonia of the years that followed the Civil War. Her literary beginnings were marked by the straitjacket of censorship and the pettiness of the Catalan cultural world under the repressive Franco regime, circumstances shared by her whole generation. Hence, several writers – Manuel de Pedrolo, Jordi Sarsanedas, Joan Perucho, Josep Maria Espinàs and Maria Aurèlia Capmany herself – even though they had already started to publish some works, opted to make themselves known through a jointly-authored book, Cita de narradors [Rendezvous of Narrators] (Selecta, 1958), which was awarded the Josep Yxart Essay Prize. In this book they analysed, linking one entry with the next, each of their literary careers.

After the 1960s, Maria Aurèlia Capmany devoted herself exclusively to the world of culture and literature, working in several genres, until she became an indisputable intellectual reference in Catalonia in the second half of the twentieth century. Iconoclastic, rebelling against the destiny that the norms had decreed was hers, she eventually came to be a public figure and, in particular, at a time in which the term "public figure", if used in the feminine form, virtually had only the negative connotations of whore, a public woman, which is precisely what she stood up for. Committed to the struggle for different freedoms, she took an active part in anti-Franco activities as a socialist and Catalan nationalist militant, first clandestinely and subsequently in official positions. Neither did she acquiesce in the role assigned to women by the Franco regime and was a pioneer in Catalonia, through her essays, in introducing modern feminism of which she was a staunch defender.

Heir of realism and influenced by existentialism, Maria Aurèlia Capmany had no wish to defer to the dictates of any literary mandarins in her own creative work. Heterodox, a booklover, a woman of great vitality and passion, instead of keeping quiet, which is what females of her times were supposed to do, she expressed herself loud and clear with impudent lucidity that clearly bothered many coteries of Catalan culture. This also explains why, when 2011 will see the twentieth anniversary of her death, Maria Aurèlia Capmany is still, for these sectors, an "uncomfortable" figure and this is a situation that engenders amnesias and cultivates oblivion. Guillem-Jordi Graells, the leading scholar of her work and editor of Obra completa de Capmany [Complete Works of Capmany], has always left no room for doubt in his denunciation of this neglect and offers a very precise summary of her legacy: the diversity of her literary endeavours, her taste for controversy, her public personality on several fronts of the struggle, her accommodation to all sorts of channels for conveying ideas and her importance as an intellectual in Catalan culture after the Civil War, after the victory of Franco, which marked her so much.

The Early Works, Existentialism and Identity Crises

Maria Aurèlia Capmany was born in Barcelona on 3 August 1918. Granddaughter of the federalist lawyer and writer Sebastià Farnés (1854-1934) and daughter of the folklorist and writer Aureli Capmany (1868-1954), she grew up in a liberal, intellectual, left-leaning, Catalan-nationalist family, a background to which one must add her secondary schooling at the Institut Escola, a centre of educational renovation established by the Republican Generalitat (Catalan Government) that was to leave a permanent imprint on her. The spirit of freedom in which she was educated, however, came to an end with the defeat of 1939. With a degree in Philosophy, she began her literary career in the 1940s while simultaneously teaching philosophy and language.In 1947, Maria Aurèlia Capmany was a finalist for the first award of the Joanot Martorell Prize for the Novel, with her book Necessitem morir [We Need to Die], which was not published until 1952. She won the second award of this prize with another novel that also had problems with the censors and that was not to appear until years later, in revised form, reworked under the guidance of Salvador Espriu and with a different title, now called La pluja als vidres [Rain on the Windows] (1963). For all the trammels of censorship, Maria Aurèlia Capmany never stopped publishing thenceforth, especially novels. These early works, most of them with female characters and set outside Barcelona, are concerned with existential themes although they also present a formal focus from a fragmented psychological standpoint that is a long way from any lineal treatment, which heightens the sense of estrangement of her characters in the world, as well as a feeling of their relativity. Within these guidelines, Capmany's first novels, using a range of techniques, tell the story of different kinds of identity crises in a hostile context that has parallels with the situation of Catalonia under the dictatorship.

Capmany's fiction captures that period of social crisis, thus fleeing generalisation and settling for small instants with a tone akin to impressionist art. In order to bring out this crisis, she shuns the conventional character of psychological description, finding her narrative tools in new techniques. Like Jean Paul Sartre or Alberto Moravia, who suggest in their works that coherent positions are mere show, Capmany presents the reader with different kinds of individuality in conflict with the hypocritical social milieu they inhabit. Hence the existence of her main characters unfolds against a backdrop of false sentiments, always clashing with conventions, just as there is dissonance between the life imposed by society and the life that is desired. It is the divorce between personal desire and social imposition.

Intellectual Plenitude

In the 1960s, by which time she had published a number of novels, her activities in the domains of literature and theatre led Capmany to leave her work as a teacher. From then on, her work flourished in all its multifaceted expression. First, is her fiction writing and a series of books she produced in this phase of full literary maturity: novels, collections of short stories and commemorative prose. Second, is her work in theatre. Co-founder, along with Ricard Salvat, of the Escola d'Art Dramàtic Adrià Gual (Adrià Gual School of Dramatic Art) in 1959, director, teacher, playwright and actress (a film actress as well), she staged and published several of her own works and, with her sentimental partner as of 1969, the Mallorcan writer Jaume Vidal Alcover, was instrumental in the development of cabaret theatre in Catalonia, with a number of works that were put on in the venue of La Cova del Drac in Barcelona. In addition to these activities were her books of essays, translations, songs, her work in the mass media – scripts for comics, radio and television shows and a continual stream of articles in the press – courses, lectures, presentations, opening speeches at different events, and as a jury member for different competitions and awards. All this added up to intensive effort, which was also recognised by a number of prizes.Then again, one must also mention her political activities. A member of the Socialist Party of Catalonia, she was head of Culture in the Barcelona City Council and member of the Barcelona Provincial Council from 1983 until her death on 2 October 1991. This tireless contribution to the world of culture, which was barely interrupted by her final illness, was characteristic of her lifelong trajectory of someone who is committed to her reality and, above all, herself.

In the 1960s, Maria Aurèlia Capmany's work, now at the height of her literary maturity, evolved towards a more socially-oriented fiction, changing from treatment focused on individual to more collective affairs with historical motivations and implications. In contrast again with her earlier phase, Barcelona now becomes the setting of most of her novels and even takes on the part of a prominent character. History enables her to situate and understand the present. From different perspectives, historical inquiry permits her, with educational intent, to re-create national epochs with a view both to explaining them from new vantage points and, by means of a range of themes and motifs, to reconstructing episodes and situations with a shared characteristic: a vindicatory view of national history from the viewpoint of left-wing Catalanism, which also entails (in all her works – narrative, theatre, essay and commemorative prose) unrelenting critical irony directed at the bourgeoisie. Memory and the passing of time are among her literary motifs, indeed constant features of her work.

From the standpoint of realism and by way of several techniques, even turning to the crime novel or documentary theatre, her highly vital writing is further invigorated in its sensual evocation. Capmany's literature is realist. She loved Honoré de Balzac – of whom her mother, Maria Farnés, was an assiduous reader – Henry James and the nineteenth-century novel, yet her realism is grounded in the twentieth century and, in this regard, one should mention the name of Virginia Woolf, her impressionist style and the moments of being she created. Capmany, who liked clowning, acting and imagining other existences, found in literary creation, for her a form of diversion, the way of doing just this. Telling the story of her country, her city, her gender in her clear, direct, didactic style, permitted her, with large doses of irony and a whole arsenal of resources, to imagine other possibilities and raise doubts and problems.

Feminism

Apart from her leading role in Catalan culture and intellectual life in the latter half of the twentieth century, Maria Aurèlia Capmany was one of the pioneers in dealing with the condition of women and elaborating, in a number of essays, articles and lectures, a series of feminist theories. She was someone who fought for individual and collective freedoms, among which was equality for women. Condemned by her historic and social context to have only marriage and maternity as her life goals, Capmany spurned this destiny and constructed herself as a free, independent woman.Capmany's feminism can be situated in the international movement that emerged after the Second World War, with Simone de Beauvoir's theories as their starting point. This is a hybrid feminism, based on cultural and literary analyses of texts and myths in which women are represented, described and defined, comparing them with the female condition of the times and focusing the inquiry on the process and results of the fabrication by the patriarchy of female stereotypes and on how they persist in behaviour and social values. Capmany argues for a feminism of equality, inveighs against the sexist biases of the enlightened project of modernity and the exclusion of women from social and political spheres while at once championing a policy of parity and integration of women. These theses are sustained and expanded upon in a whole series of essays that follow in the footsteps of her 1966 work La dona a Catalunya [Women in Catalonia].

If her cultural and literary labours had considerable influence in the peer group of the seventies, her feminist theories have also left their mark in subsequent generations, as would be the case, with regard to both legacies, of Montserrat Roig. For all the time that has elapsed, Maria Aurèlia Capmany's theories and approaches are still totally valid for understanding the historical evolution and the present juncture of the situation of women, their identities and analyses of the female subject.

Copyright © 2010 Montserrat Palau