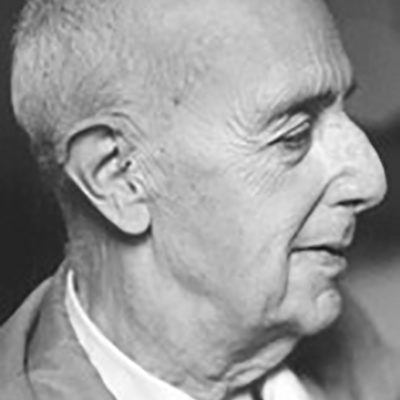

Llorenç Villalonga

Jaume Pomar

Llorenç Villalonga (1897-1980), born in Palma de Mallorca, was a multifaceted man of letters. As a psychiatrist, a profession he practised all his life in the island of Majorca, he was capable of capturing the moods, the moments and the whys and wherefores of the human soul in a unique way. His novel Bearn (published in English as The Doll's Room) is without doubt one of the great twentieth-century works of Catalan literature. Essentially, it is a reflection on the passing of time and the effects of this on individuals (the myth of Faust applied sui generis to a Mallorcan nobleman) and society (the decline of the minor rural nobility).

The life and work of the controversial Mallorcan writer Llorenç Villalonga Pons reveal three quite distinct and often contradictory stages, each of which merits separate consideration. In fact, however, he was also the sum of his career and the result is highly visible: fifteen novels, five collections of short stories, five volumes of plays and more than 1,500 newspaper articles. Distributed over a half a century of active life (1924-1975), this oeuvre, if contemplated in perspective, is somewhat proteiform, its shifts activated by the ferment of constant evolution. Better said, in trying to make an approximation to his weltanschauung, one might speak of the three differentiated cycles as if they were three concentric circles - three serpents eating their tails - traversed by the common axis of existence itself, which was solicited by different forces over the years.

Villalonga chose to study medicine in open opposition to his father Miquel Villalonga Muntaner, a military man by profession who would eventually reach the rank of general. After declining the possibility of a career in the Church or as a lawyer, Llorenç Villalonga decided on Medicine, a profession that was well-established in the family of his mother, Joana Pons Marquès, who came from Maó in Menorca.

He began to write for the newspaper El Día de Palma when he was still a student at the University of Zaragoza, where he would obtain his degree in 1926, after having studied in the faculties of Medicine in Múrcia (1919), Barcelona (1920-23) and Madrid (1923-24). This journalistic writing was the opening of his first literary phase (1924-1939). He started out as something of a snob, inquiring, curious and attracted by any novelty or avant-garde tendencies. He had cut his literary teeth reading Anatole France, Voltaire, Freud, Ortega y Gasset, and some of the writers of the Generation of '98. A little later, in 1925, Damià Ferrà-Ponç tells us, he discovered the work of Marcel Proust, which was decisive when it comes to considering the major influences on Villalonga's fiction. In this early stage, he produced a considerable number of short stories - later to be collected, reworked and translated into Catalan - along with quite a number of literary, artistic and cultural pieces. This was the high point he would never go beyond in the domain of journalism. However, much more important is his novelistic debut when he irrupted on to the scene with Mort de dama (Death of a Lady, 1931), written in Catalan and with a prologue by Gabriel Alomar Villalonga, an event that would earn him the eternal enmity of the regionalists and, above all, the writers of the Mallorca School. He also took over as literary director of the review Brisas (1934-36) where he would bring out five short stories, the play Silvia Ocampo and the beginning of Madame Dillon, a novel which would finally be published in its complete form in 1937. This novel, the play and the tragedy Fedra (Phaedra, 1932), reveal how deeply he was affected by his relationship with the Cuban poetess, Emilia Bernal. These three works that Jaume Vidal Alcover called the "Phaedra cycle" were initially written in Spanish but later underwent thoroughgoing metamorphosis and were translated into Catalan by the author. They constitute quite an accurate document of tourism in Mallorca before the Civil War and the transformation that this had wrought in the traditional forms of life in the island society.

More interesting still is Mort de dama, which is regarded today as a classic of contemporary Catalan letters. Villalonga produces, with the deathbed of the aristocrat as his pretext, an affidavit of the collapse of a Mallorca that is dying with her. He constructs this period fresco through a number of paradigmatic characters, true archetypes of the time. The author's ambivalence towards the world of the Mallorcan botifarres [the local aristocrats - also known as botiflers - who were partisans of Spain, the name dating from their support of Felipe V - translator] is manifest in the dualism represented by dona Obdúlia Montcada and dona Maria Antònia, Baroness of Bearn. The former is crude, libidinous and vulgar, while the latter is elegant and discreet, a paragon of the old culture. Dona Obdúlia's demise also brings forth other characters that are typical of the island world. There is Aina Cohen, the repressed xueta [a descendent of converted Mallorcan Jews] poetess, through whom Villalonga satirises the island's noucentista [referring to a turn-of-the-century movement of cultural renovation] poets of the Mallorca School; the Marquis of Collera, who is adorned with all the ineptitude of Mallorcan Restoration politics, if not of all time; and a chorus of middle-class voices from the ranks of government in the secondary characters who are caricatures of themselves. A long way from this, in another part of the old city, in Gènova and El Terreno, there is a new and restless world of foreigners speaking barbarous tongues, in which the women smoke, drink whisky and swim in winter.

Through these characters, Villalonga constructs a satire on Mallorcan life in the 1920s. A grotesque, offensive satire for which he would not be forgiven. Later, the Civil War was the background to a period in which the author temporarily became a fascist supporter. He was bedazzled. This fact, along with a number of lamentable episodes and a touch of perversity, aggravated the tensions that already existed between this major writer and the denizens of the political and literary regional establishment.

Some months after the Franco uprising, he married a distant relative, Maria Teresa Gelabert Gelabert, who was both rich and eminently sensible. This union - a marriage of convenience - closed the door to the period of his youth and adventures. Maturity came with his abandonment of Dhey [his pseudonym], the snob. Satire gave way to elegy in his work with his lengthy account of the myth of Bearn. The new phase (1939-1961) was dominated by memory, its driving force and central strand, as he devoted all his creative energies to writing his vast personal memoirs and about the characters and events around him. In this project he was guided by a Proustian observation to the effect that "The only paradise is a paradise lost".

After a time of silence in the early 1940s, he began again, in 1947, to write for the press, in the newspaper Baleares, which had emerged from the fusion of El Día and Falange, once again using his pseudonym of Dhey but now the content of his writing was quite different. Predominant in his writing are two post-war themes, the civil and international domains. He has seen the ruination of his world and shows a clear desire for peaceful coexistence and harmony with the immediate environment. A shaken Europe has rent the frail, subtle fabric of its culture. And Villalonga begins to fear the consequences of this, is terrified by the disorder, the madness he contemplates every day in his work as a psychiatrist, and the superstitious magic and irrationality of the times.

With his change of heart came new friends. Manuel Sanchis Guarner, the Valencian philologist who had suffered greatly from reprisals at the hands of the Franco regime, became a habitué of Villalonga's group. And he would actively promote his rehabilitation in the world of letters. Sanchis would bring about the reconciliation with

Francesc de B. Moll, who would then be Dhey's first publisher after the Civil War when he brought out La novel·la de Palmira (Palmira's Novel, 1952). In Palma's Cafè Riskal, Villalonga suddenly found himself surrounded by the young writers of the 1950s, Llorenç Moyà, Josep M. Llompart and, in particular, Jaume Vidal Alcover, who was his great friend between 1951 and 1968. Moreover, with this return to the world of the book, he now enjoyed the support of Salvador Espriu, an old friend of the pre-war days who would write the prologues to La novel·la de Palmira and the second edition of Mort de dama (1954). In his incisive prose, Espriu not only defends the writer but also the human figure of the novelist from Mallorca who was still beyond the pale for right-thinking people.

He wrote the novel Bearn, in Catalan between 1952 and 1954 but, a few pages short of the end, he rebelled at the stylistic changes the Barcelona publisher Editorial Selecta had made to Mort de dama. Irritated by this, he translated all the work he had done on Bearn into Spanish, writing the end directly in this language. This novel, the veritable chef d'oeuvre of all his production, was not very successful at first. Underappreciated in two literary competitions, it was published in 1956 with a short print run of only a thousand copies without attracting the attention of critics or readers. Later, with the Catalan version of 1961, it received the praise it deserved. Winner of the 1963 Critics' Prize, it was given second place in the list of the major works of Catalan fiction after the Civil War in a 1964 survey carried out by the review Serra d'Or, while in 1966 it was the centrepiece of Volume One of the Obres Completes (Complete Works) published by Edicions 62 with a prologue that was a major piece of writing by Joaquim Molas. This volume entitled El mite de Bearn (The Myth of Bearn), appeared in a collection called Catalan Classics of the Twentieth Century, a significant fact for more reasons than one.

Bearn has been translated into almost all the major European languages and also into Chinese and Vietnamese. The film version by Jaime Chávarri has also given international presence to the novel.

At the same time, in the 1960s, Villalonga embarked on his third phase (1961-1975) which lasted until the end of his active life as a novelist. In this period, alongside major autobiographical works, he published others of less interest, for example the books that comprised the "Flo la Vigne" cycle. This figure, the literary version of the writer Baltasar Porcel, was the main character of a major short novel called L'àngel rebel (The Rebel Angel, 1961). In its second edition the name was changed to Flo la Vigne (1974) and it lost some of its earlier charm with the additions that had been made. Outstanding among the autobiographical writing of this stage are Falses memòries de Salvador Orlan (False Memoirs of Salvador Orlan, 1967), Les fures (The Ferrets, 1967) and, in particular, El misantrop (The Misanthrope, 1972), where he reconstructs his youthful experiences as a student in Zaragoza with a group of friends from the Basque, Navarra and Rioja regions of Spain.

The three works of the "Flo de Vigne cycle", La gran batuda (The Great Raid, 1968), La Lulú o la princesa que somreia a totes les conjuntures (Lulu, or the Princess Who Smiled on Every Occasion, 1970) and Lulú regina (Lulu Regina, 1972), heralded a retrogressive, erosive process in Villalonga's thought that opposed modernity in its every aspect. These books reveal an ideology that is against the advance of industrialisation and machine technology, as the author rails against the consumer society, in the same way as he does in his articles for Diario de Mallorca, El Correo Catalán, Lluc, Destino and Serra d'Or.

Nonetheless, success was with him at the end. Andrea Víctrix (1974) obtained the 1973 Josep Pla Prize, and he brilliantly brought to a close his career as a novelist with Un estiu a Mallorca (A Summer in Mallorca, 1975), the narrative version of his stage drama Sílvia Ocampo, which goes back to the 1930s, recalling his relationship with Emilia Bernal at the end.

Copyright text © 1999 Ediuoc/ECSA