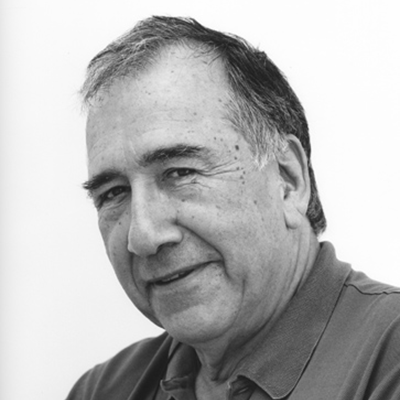

From a Felicitous Point

Francesc Parcerisas

Sanaüja, 1938. Poet and arquitect

Throughout its long and supple existence, Joan Margarit's poetry has kept acquiring more and more readers so that he has now become one of the most widely read Catalan poets in Catalonia and also in the rest of the Peninsula. His early works were written in Spanish but he would eventually switch to Catalan. His poetry is realist with a strong presence of autobiographical elements, a well-tempered use of metaphor, and reflections of a moral nature that move from the individual to the collective. In Margarit's work, anonymous individuals and jazz musicians might be the protagonists of a poem.

Joan Margarit (Sanaüja, 1938) has reached the felicitous point that now enables him to harvest the fruit of many years of work, of what -to paraphrase him- he has done, rather than what he thought he ought to do. Margarit's literary engagement, moreover, has markedly increased in recent years thanks to his intensified focus on writing, his study and translations of the work of other poets (Hardy, Bishop), translations and diffusion of his own work and, with all this, achieving a register of truth, which, while it has been present in all his books, has acquired the transparency of knowledge and pain. Càlcul d'estructures (Calculus of Structures), 2005 and Joana, 2002 -and I believe that, they should be presented in this order because the former of the two titles was left dormant as a result of the urgency of the latter- very effectively advance this calm, uncompromising accrual, the poet always comfortable in the structure of his verse, and revealing a good dose of moral firmness that has no time for deceit, especially deceit fuelled with false illusions that mask the sense of life, which is nothing other than the Casa de Misericordia (House of Mercy). Poems like "La merla" (The Blackbird) or "Refugis" (Refuges) are constructed in order to accompany readers and the poet, from his full understanding of having saved very few things. He now repeats in this new book, "There remained what lay behind tenderness" and we understand that not even tenderness -not to mention blinding passion- can be any life-saving plank to which we might cling.

Cast adrift, inevitably, on the sense of life, we waver between the black mask that blocks out the light, enabling us to long for some kind of rose-tinted patch of life, and the deep, inexorable knowledge of the insignificant certainty of our own end. The only possible way to contemplate past life, for Margarit, is the ability to "manage one's own desire and one's own failure". Such stoicism, in the end, has to be cruel "like a good poem", or cruel like the hair-raising reality of the theme that runs through the architecture of the writing that gives its name to the collection: in the years just after the Civil War, children were put into the House of Mercy by mothers who were reduced to conditions of the most abject poverty. "True charity is frightening", reflects the poet. Margarit's work, from L'ombra de l'alta mar (The Shadow of the High Sea -Edicions 62, 1981) and Cants d'Hekatònim de Tifundis (Songs of Hecatonimus of Tifundis 'La Gaya Ciència, 1982), which surprised Catalan readers (although Margarit had already published four volumes of poetry in Spanish, among them Crónica (Chronicle -1975), in the prestigious Ocnos collection of Barral Editores), has become more singular and intense, very personal, with a world that, even while often non-transferable, states very clearly what lies behind the emotions of today's citizens. The private haven affords us with moments of passion that, with luck, become moments of knowledge. And knowledge itself warns us that neither passion nor knowledge can last, however hard we try to make them. Against this nihilistic perspective, the only struggle, in Margarit's case, is the saving grace of writing itself: feelings, memories, the experiences of different moments, music, readings? Behind his comprehensible and homely images there yearns an old-style humanism, without uninhibited tragedies but closer to humble mystery and the sense of fragility that accelerates as time devours us. "Tramvia" (Tram), "Crematori" (Crematorium) and "L'últim joc" (The Last Game) are examples of this way of working, which manages to shun deceit and proceed with firm step on foundations that the poet knows his readers will work out for themselves, if not in the reading, then in the memory of the poem. The slippers of an old man, the oily sea at the foot of the cemetery, the old tractors in the countryside, the dignity of the old man who knows he's nearing death ? are notes, images for a single idea: navigating with dignity the buffetings of life.

One final consideration: the wide diffusion of Joan Margarit's work is an example of his personal tenacity. The appearance of his most recent books, translated by himself, in well-distributed collections of Spanish poetry, and his contacts with writers in Spain who appreciate his work and have accorded him recognition that is evident, for example, in the bilingual volume of Letras Hispánicas (Hispanic Letters -edited by J. L. Morante and published by Catedra). And the support he has received from the poet Anna Crowe, and his close collaboration with her in the English edition of Tugs in the Fog have been important factors in the book's being this autumn's recommended translation by the English Poetry Society. Paraphrasing some lines of the poem "Últims combats" (Final Battles), we could say that we should believe, for once and for all, that from the patched-up mesh of our culture it is still possible to extract such a beautifully effective desire for communication as Margarit's.

Copyright text © 2007 Francesc Parcerisas