The Obscure Province

Julià Guillamon

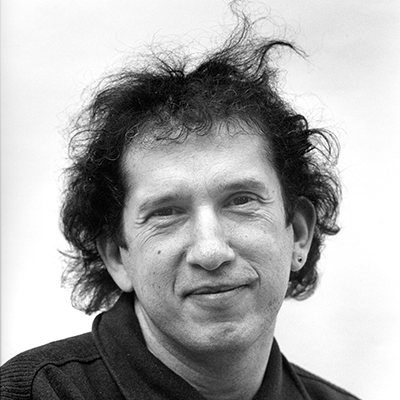

Joan-Lluís Lluís (Perpignan, 1963), journalist and novelist, is one of the most notable writers in French Catalonia. His oeuvre, written exclusively in Catalan, is a unique and remarkable voice of new Catalan fiction. The Day of the Bear was awarded the prestigious Joan Crexells Prize in 2005.

Joan-Lluís Lluís is the author of five novels and the brief collection of essays entitled Conversa amb el meu gos sobre França i els francesos (Conversation with my Dog about France and the French - 2002), which marks a turning point in his work.

Els ulls de sorra (Eyes of Sand - 1993), Vagons robats (Stolen Carriages - 1996), Cirera (Cherry - 1997) and El crim de l'escriptor cansat (The Crime of the Weary Writer - 2000) all have, as a common element, the voice of a narrator, a character who breaks the rules. In the first novel, this is an old Arab sergeant, survivor of the Algerian War, and witness to the crimes of a military man who is the National Front candidate in some municipal elections in Normandy. In Vagons robats it is a boy from Provence who runs away from his village and family. He has worked for the railways and is entitled to free transport in the SCNF network. He travels all over France for a year, doing odd jobs and stealing in trains. Cirera is the diary of a girl who is uninhibited about sex and her account of it, which enables her to shake off her emptiness and boredom, hints at a dark, unhealthy side of her character. El crim de l'escriptor cansat brings two complementary characters into confrontation. The first is the police inspector Ximenès, who is the son of a Gypsy and from Provence. He wants to be a writer and breaks police rules to get to know the novelist Pierre Alessandri, who is suspected of killing his wife, in order to blackmail him. The novel written by Alessandri (under the name of Ximenès) is about a Catalan soldier, Adrien Farines, who died of his wounds in the early days of World War One. His name appears in the list on a monument honouring the dead in the War, the monolith of Oms, which according to Lluís in Conversa (Conversation) is a symbol of Catalan submission in France.

Joan-Lluís Lluís's characters are outsiders who cannot fit into the reality around them. The fact that they exist and that we find them writing represents an attack on the order that has been imposed by the powers-that-be in the province. Driss Mehamli is killed. Ximenès (who is possessed by the absurd idea of supplanting Alessandri) becomes an object of ridicule in a devastating campaign when it is found that his novel has been plagiarised from a Belgian work published in the 1920s. Lluís portrays a fractured world. And the fact that we never discover what causes the cracks heightens the sense of strangeness. He describes the criminal behaviour of the military who took part in the repression of the FLN, the lack of consistency in young people and in provincial life, the urge to live another kind of life, the impossibility of doing it, and the impunity of those who opt for collaborating with the powers-that-be. All his novels present an asphyxiating situation, building up to a dramatic ending. I think it is quite significant that it is only in the first, Els ulls de sorra, that the main character finds someone to talk to, in this case a young journalist who takes down Driss Mehamli's declarations before the National Front thugs kill him. In Vagons robats this possibility of having an interlocutor has disappeared. Antoni Bellefargues writes eleven letters to a girl he met during a brief stay in Brittany, revealing significant aspects of his life. The letters never reach their destination. They are like the briefly flaring matches lit by Bellefargues and his partner for the night when they are fooling around in the Irish Tavern of Saint-Malo. In El crim de l'escriptor cansat, Ximenès' relationship with Alessandri and with his friend Picard (the corrupt policeman who has changed sides to live off prostitution and drug-dealing) is not one that can be regarded as consisting of successful acts of communication. Ximenès is a frustrated character who, bearing the stigma of having a Gypsy father feels discriminated against when he is in Paris and, despite the temporary success he achieves as a writer, he never manages to overcome the feeling of inferiority and shame that the capital brings out in him.

In El dia de l'ós (2004) we once again find some elements of the earlier novels. After El crim de l'escriptor cansat, Lluís published his anti-French pamphlet thenceforth introducing into his work a reflection on the mechanisms of French domination in North Catalonia. Like Antoni Bellefargues in Vagons robats, Bernadette, too, has fled from the prison-like atmosphere of her village. In both cases, the flight has originated in an obscure sexual affair. However, while in Vagons robats this is an unconfessable episode, revealing a lack of moral fibre in Bellefargues, in El dia de l'ós it is an almost insignificant event, of fairly innocent eroticism, which people then use to stigmatise a girl. Bernadette goes to live in Barcelona, which, for the inhabitants of Vallespir, is a taboo place. Another of the elements that Lluís returns to in this work is oral storytelling, a key element in Els ulls de sorra (with the fantastic stories told by Aït, one of the soldiers in the FLN detachment) and also one that establishes a counterpoint in El crim de l'escriptor cansat, with the case of the dead soldier who, after the war, had lived on in popular memory and whose story Alessandri reconstructs on the basis of documents of the time. The outsider existence of the main characters has a parallel in the imaginary world, where we find the same signs of repression as in the real world, so that it never represents a way of escape. In the case of El dia de l'ós the plot revolves around a popular tradition that Lluís elaborates and transforms: the day the bear returns to the mountains of Prats de Molló, it will come down to the village and carry off a young girl and then the inhabitants will be free of the French. What in the earlier novels is an undefined fear is specified here. The novel deals with the fear of living in freedom, the impossibility of liberating oneself from submission, of breaking the circle of social, political and sexual repression that dominates the characters. One of the highlights of El dia de l'ós is the dual time sequence that creates enigmatic moments of intersection.

In Vagons robats, above all, but also in Cirera and El crim de l'escriptor cansat, there are some reflections about the family with its significant implications in the psychology of the characters and, going still further, in an idea of the history of North Catalonia since the Treaty of the Pyrenees, which is discussed in Conversa. At some point, the fugitive boy, the strange girl and the dreamer policeman, sum up their lives, an evocation that brings out the distance between the world of their Provençal or Catalan grandparents, who conserve the language and the old customs but without wanting to pass them on, and that of their rootless French parents, who are anaesthetised by a false sense of well-being. The grandchildren, who are the main characters in the stories, have lost any points of reference that might enable them to live in harmony with the territory. They are part of a world that is becoming extinct, with only a vague memory of the old traditions, and this rootlessness turns into lethargy or violence. At the same time, they feel profoundly strange in the outside world in which they find themselves (in Paris, Bellefargues and Ximenès feel unbearably upset). In El dia de l'ós this family setting is reproduced in the character of the mother who has gone mad and the brutalised father who have not been assimilated by the invaders and who lead a semi-savage existence. The animalised mother breaks up logs with an axe while the father holes up in a ruined farmhouse. This time, Lluís extends his temporal framework, going back to beyond the grandparents' times, to the period of the Salt War when Josep de la Trinxeria thrashed the French troops before being routed himself by Marshall de Chamilly in 1670. The novel superimposes the reality of Prats de Molló as it is today with war scenes of previous times, in a way that recalls what Marco Ferreri did with Touche pas la femme blanche or Buñuel in Cet obscur objet du désir. History impinges on the present and legend alters the course of everyday life. The whole charge of anxiety and violence, rancour and desire, is concentrated in a key moment, the Sunday of Carnival, the Festival of the Bear, which stirs up the collective unconscious, unleashes instincts and brings about an explosion of freedom that will end with the triumph of civilisation and the impossibility of going back to the old order.

The fiction that Joan-Lluís Lluís has written since 1993 gives the impression of revolving around an empty nucleus, an invisible centre, tracing the orbital movements of the characters. El dia de l'ós once again describes the problem, giving it form and a name.

Copyright text © 2006 Julià Guillamon