Gerard Vergés, a Different Writer

Jaume Subirana (UOC)

I've already said elsewhere that I owe my discovery of the work of Gerard Vergés to Xavier Bru de Sala, who was literary director of Edicions Proa in those days and, without a doubt, a prime mover in the poet's being awarded the Carles Riba Prize in 1981. He also wrote the Prologue to L'ombra rogenca de la lloba (The Reddish Shadow of the She-Wolf). In 1982, the present writer was a mere wolf-cub who made it his business to buy all the poetry books he possibly could in the endeavour of learning "how to go about it", but even I could see clearly that a book like that one –a single poem of more than 300 verses signed by Romulus with an array of notes contributed by Remus– was radically original, atypical, unclassifiable and, with (or because of) all that, was a breath of fresh air in Catalan poetry at the time (when, it must be said, one didn't find much that might have been called exemplary). In fact, L'ombra rogenca de la lloba and its author were hard to pigeonhole then and they continue to be so even now, more than quarter of a century later.

The Appearance

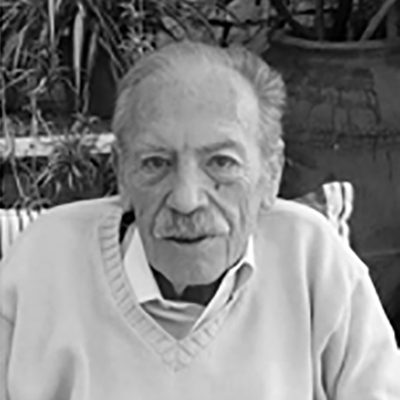

The figure and the poetry of Gerard Vergés (I've come up through a tradition that clearly distinguishes between the two but, at the same time, besides the poetry, I've become increasingly interested in the human figure of artists, their biographies, their characters and their personal stories), both the figure and the poetry of Vergés, as I was saying, seen against the background of the rest of the fraternity, point to the trait of distinction rather than to that of similarity. And this might be neither good nor bad... or maybe it is one or the other. However, let us not jump too far ahead but go back, rather, to the point of distinction, of difference: to character and, hence, uniqueness. As far as the ordinary reader was concerned, on that Saint Lucy's Eve, twenty-seven years ago now, Vergés suddenly irrupted right at the top, bearing off the plum of the literary prizes in our poetic circles: without any previously recognised literary curriculum, without having been quoted, and without patrons who might have made him "ascribable".Tortosa, 1931-2014. Doctorate in Pharmacy, poet and essay writer

Furthermore, he made his appearance, as I have noted, with a long book consisting of only one poem, a piece that was also, among other things, meta-literary, playful, ironic and, at some points, even a spoof on himself. Beyond this particular book, Vergés' poetry had (and still has) a texture that is at once cultured and light-handed, ironical without ever seeming cynical, learned but not pedantic. This poetry, it is worth repeating, is hard to slot into familiar groups and trends. To top it all, he is an outsider (from Tortosa!) but I shan't be the one who, at this point, divulges the extent to which Catalan culture –including literary culture– is centralist. Then again, although this might seem anecdotal, one of the first things I learned about him, before as much as opening any of his books, was that Vergés was a pharmacist: in a tradition wherein the figure of the poet tends to be located in some fuzzy limbo between the models of Catalan-language-teacher-passing-though-poetry and dilettante rentier, that real-life profession, that other life among substances and formulas and laboratories made him –what would you expect?– more credible for me, less cardboard cut-out. However, the definitive touch came later but I was unaware of it until some time had elapsed because what happened was that, with his first book, Gerard Vergés came, conquered and went back, which is to say he came bearing no plan of conquest, or reform, or evangelisation of Catalan poetry, with no hot cakes to sell, no dogma to impose. That certainly was different. That certainly was something to be grateful for...

Eventually, I got more and more involved in this business of reading and writing and, together with two friends as irresponsible as myself, began to write reviews of Catalan books for La Vanguardia under the pseudonym of Joan Orja. Thanks to the magnanimity of Robert Saladrigas, we were taking on increasing responsibility, to the extent that we were being sent the galley proofs of books by winners of major prizes before their books appeared. The challenge was exciting. We had to discuss these works from scratch (in a hurry and with no other opinion to refer to) and the uneasiness over titles that we may have wished to avoid was amply compensated for by the joy of the "discoveries"... Thus it was that Gerard Vergés cropped up in my life for the second time when, in 1985, he was awarded the Josep Pla Prize offered by Edicions Destino, and it was the task of Joan Orja to review his Tretze biografies imperfects (Thirteen Imperfect Biographies). If you don't already know it, I fervently recommend this book. It was one of the surprises, one of the good memories I have of that stage as militant critic. In Tretze biografies imperfectes Vergés, the writer who'd set about getting Romulus and Remus to speak in verse, is a mocking presence behind the subjects of his biographies (from the Inquisitor Don Fernando Niño de Guevara to Circe, daughter of the Sun, by way of Giorgio de Chirico and the outlaw Panxampla) as a voice that is –yet again– cultured, intelligent, modest and ironic (I know you can't be ironic without being modest but so many folk arrogantly believe that they are ironic that it's worth repeating).

Next came two more books of poems: Long play per a una ànima trista (Long Play for a Sad Soul) in 1986 and, in 1988, Lliri entre cards (Lily among Thistles), which includes the emblematic "Art poètica" (Poetic Art), the beginning of which cries out to be cited:

Si quan escrius, amic, ets tan il·lús,

que penses que la rima i la mesura

són el secret, infausta singladura

li espera al teu vaixell pel trobar clus.

El mot obscur i el pensament difús

segur que et cavaran la sepultura.

Poeta ver no fa literatura.

La retòrica, amic, és com un pus. [...]

If when you write, friend, you're so illusion fraught

that you want to believe that metre and rhyme

are the key, the day's end will be a blighted time

when your boat must hie back and find its port.

The unfathomable word and hazy thought

will surely be digging your grave in grime.

The true poet does not literature mime.

Rhetoric, my friend, comes forth like pus, in short.

After that, he published a volume of short essays Eros i art (Eros and Art – 1991, winner of the 1990 Josep Vallverdú Prize), which was followed by a veritable touchstone: his complete translation of Shakespeare's Sonnets, which was published and re-launched in a widely-read collection and recognised with the "Crítica Serra d'Or" Critics' Prize. A further book of poems was subsequently published, this time with the title La insostenible lleugeresa del vers (The Unbearable Lightness of Verse, 2002), and then came the monumental bilingual edition of his complete poetic works in Spanish, La raíz de la mandrágora (The Mandrake Root, 2005), a publication for which we cannot be grateful enough to its publisher (Juan Ramón Ortega) and translator (Ramón García Mateos).

Triple Life and Literary Programme

In the midst of all this, Gerard Vergés, like a hero of yore, continues to be, for me, the immutable emblem of the de luxe outsider, the wise and happy man, in harmony with his place, his times and his life, and yet engaging in continuous dialogue with his own world, which is that of his classics. Some years ago, referring to Lliri entre cards, I wrote: «The poetic guild of this country has often been accused (and probably fairly correctly) of being boring, unintelligible and presumptuous. Well, the best thing that can be said about Gerard Vergés' most recent book is that it challenges each one of these clichés: the reader enjoys reading it, the poems are written in such a way as to be understood, and the poet who emerges is one that pokes fun, is alive and rich yet without the slightest trace of vainglory. You imagine him halfway back from almost everything, either sitting in the back room of a shop or some comfortable living room lined with books and paintings, a smile on his lips and an ancient athlete's sense of fair play, running now only for the pleasure of it, to get some exercise and a glimpse of the thighs of pretty girls.» I'd sign that piece again today but would add more emphatically my satisfaction that our culture has people like him and would stress my admiration for his triple life and literary programme: the conviction (and experience), first of all, that discretion is not opposed to ambition; second, that wisdom does not inevitably go hand in hand with pedantry; and, third and finally, that literary pleasure is good, long-lived, is true and it makes us more human... To put it in literary terms –and I hope you'll excuse a touch of pedantry– to Shakespeare from Tortosa (or to the universal through the particular, as Josep Carner would say), always with a grateful smile on the lips.We've said (I mean I've said, since I don't want to hide it), then, that he is not of the centre, is discreet, cultured, intelligent, ironic, a de luxe outsider, a happy savant... There is a fragment of Walter Pater's The Renaissance (translated into Catalan by Marià Manent and published –a miracle of sorts– by the Institució de les Lletres Catalanes (Institute of Catalan Letters) in November 1938), in which Pater, author of those magnificent "Studies in Art and Poetry", which were to become a nineteenth-century classic, evokes Lessing's Laocoön in order to speak of Giorgione:

«Now painting is the art in the criticism of which this truth most needs enforcing, for it is in popular judgments on pictures that the false generalisation of all art into forms of poetry is most prevalent. To suppose that all is mere technical acquirement in delineation or touch, working through and addressing itself to the intelligence, on the one side, or a merely poetical, or what may be called literary interest, addressed also to the pure intelligence, on the other: this is the way of most spectators, and of many critics, who have never caught sight all the time of that true pictorial quality which lies between, unique pledge, as it is, of the possession of the pictorial gift, that inventive or creative handling of pure line and colour, which, as almost always in Dutch painting, as often also in the works of Titian or Veronese, is quite independent of anything definitely poetical in the subject it accompanies. It is the drawing – the design projected from that peculiar pictorial temperament or constitution, in which, while it may possibly be ignorant of true anatomical proportions, all things whatever, all poetry, all ideas however abstract or obscure, float up as visible scene or image: it is the colouring – that weaving of light, as of just perceptible gold threads, through the dress, the flesh, the atmosphere, in Titian's Lace-girl, that staining of the whole fabric of the thing with a new, delightful physical quality.»

And would what this be if not authentic pictorial (or poetic, if you prefer) quality, a silent plunging into the damp forest of pines and junipers in autumn when, hearing a sound from behind, you ask, «Is that you? / I am wrong, my love. / It was drops falling from the leaves» ("Bosc de tardor" – Autumn Forest)? It is in this sense that I wanted to speak to you of Gerard Vergés as a different writer: because he has savoir faire, because when I think of him I think of painting and I think of the Renaissance. Our possible Renaissance: the one that didn't happen, and the one that perhaps –who knows?– is still waiting for us.