My Poetry

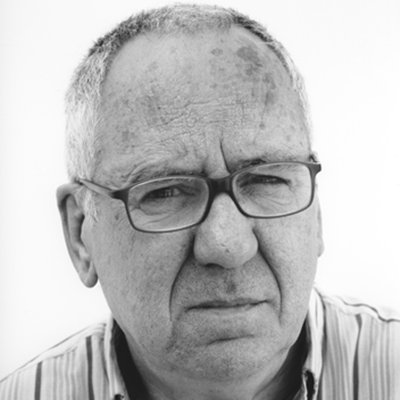

Feliu Formosa

After a public reading of my poems in Girona, one member of the audience observed that my conception of the poem was often very theatrical, as if the surrounding realities constituted some kind of stage set. I'm not aware of this but the opinion amused me. There is a book of mine that is concerned with theatre. It's called Per Puck [For Puck], a title that refers to the mischievous imp of Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream, and it is dedicated to the students who took part in the workshop I ran on this play. Per Puck, published in 1992, is the tenth of my books. It consists of twenty-eight units containing quotes from plays, written in poetic prose in which the specific experience of theatre that I want to relive is situated within a vital poetic context and, to end the book, there is a poem in which this experience is transcended at the lyrical level. In each section, some play that I have seen is recalled. It is a review of my experience as a spectator, the story of a coexistence with the world of theatre and of an apprenticeship. It goes from the Greeks through to Kantor, with Shakespeare as a significant presence. I gave a lot of thought to this book, writing it in keeping with an earlier project. This kind of thing happens quite often with me, even when the project does not require such a strict structure. To give one example, Llibre de les meditacions [Book of Meditations], written in 1973, aims to set up an exchange with Cesare Pavese and Gabriel Ferrater, two poets who killed themselves in difficult times, and all the poems are written in hexasyllabic verse, a kind of short verse that evokes that in Pavese's Death Will Come and Will Have Your Eyes. I also use this unitary formula in Semblança [Sketch] and in Al llarg de tota una impaciència [Through a Whole Impatience] (1994), in which I strive to synthesize my entire poetic world within a relatively brief type of poem. Formally speaking, this, too, is another unitary book. And the penultimate one, Immediacions [Immediacies] (2000), consists of two hundred and fifty poems of just one verse.

When I began to publish poetry, I was soon seen as an outsider and I still consider that I am that. I believe that my poetry has become increasingly stark and spare (clear, but not simple or facile, I hope). Someone has spoken of "intensive realism". Someone else has mentioned "expressionism". I have no choice but to move between Trakl's daydreams and Brecht's realities. Of all my books there are two that I really love: Semblança and Al llarg de tota una impaciència. But there's another one that is as if I didn't write it, as if it had come into being without my willing it. I refer to Cançoner [Songbook], which was written some months after I lost my partner, Maria Plans. In fact Cançoner was adapted for the stage in 1981, with music by Carles Berga (the composer of El retaule del flautista [The Tableau of the Flautist]), who wrote a magnificent piano score. The idea of staging it was Marissa Josa's and she sang the twenty poems accompanied by Carles Berga himself, with appearances by the ballerina Montse Vidal. The sets were done by Carme Vidal. After my last book, Cap claredat no dorm [No Brightness Sleeps], a title taken from a poem by Paul Celan, a poet I have up on a pedestal, I'm presently working on a dramatised reading of the articles that Montserrat Roig wrote for the newspapers El Periódico and Avui. I'm doing this with the people from the Ateneu Popular (People's Cultural Centre) of Nou Barris. It's as if I'm going back to my origins, or maybe not. Maybe I'm just moving in a terrain that has always been familiar to me. I don't know if I'll ever write another book of poems. I don't know if I'll ever act again in any professional stage work. And in this not knowing anything, there is still room for everything... until the day when, inevitably, there will be no room for anything.

Copyright text © The author and Laura Fernández Jubrías, Feliu Formosa. Teatre i paraula [Feliu Formosa. Theatre and Word] Institut del Teatre, Barcelona, 2003