The Man Who Describes the World

Francesc Canosa Farran

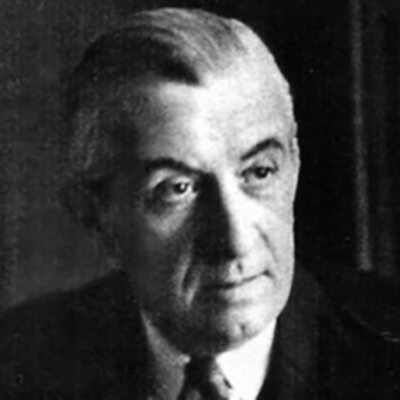

Barcelona, 1888 - L'Ametlla del Vallès, 1973. Journalist, career diplomat and translator

Whatever the point in his life, it seemed that Eugeni Xammar had lived it all. In a long interview of 1933, the young journalist Domènec de Bellmunt inquires, "Do you still have some dream you'd like to come true?" Xammar answers, "The first dream comes to be like a basic assumption. You will understand that it would be good for me, like the bread I eat, to be able to enjoy my little house in L'Ametlla with a certain degree of calm..." But it was not to be. He was 45 years old, had already described half the world and he still had forty years of life to go on describing it.

Xammar, for both the generation before the Civil War and the one that came after it, is a name that is perennially admired. In 1967 the critic Joan Triadú writes in the review Mirador, "Eugeni Xammar, a totally legendary character for those of us who are still under fifty, is a famous journalist and one I should like to meet". The legend does not die away. Just one year before his death in 1972, the young Montserrat Roig interviewed him for Serra d'Or and was captivated by this "sentimental, sceptical wolf". Yet, it was almost fifty years earlier, in 1927, that a youthful, vigorous, passionate Josep Pla waxes lyrical like never before in Revista de Catalunya: "Xammar has taught me more than all the books put together. He's the most intelligent man I know, the one with the surest eye and the vastest knowledge of the world. Moreover, he's the most human type of man I've ever come across, the least primeval, the man of most alert reason and clearest judgement. No day goes by without my thinking of him, of what he's said and, above all, of what he's suggested to me" (part of the correspondence may be found in the book Cartes a Josep Pla [Letters to Josep Pla]). Pla, the man from Llofriu, was one of his great friends and the one who, with crystalline precision, dubbed him "super-journalist".

Xammar is everything: the self-made man, of the "globe-trotting ilk" (he speaks seven languages and writes in five) with an "observant spirit of extraordinary acuteness", fast, well-informed, producing writing that is nothing short of electric. He always saw what had to come about. He was the prototype of the modern journalist. He bore inscribed on his face what had to happen in the planet. And, of course, he described it.

The shop boy in a company of cotton products becomes a journalist at the age of sixteen. It is 1904. A youth with a "leonine head of hair" makes his debut with the Catalan nationalist weekly La Tralla, one of those combative publications that is open one day and shut down the next. Metralla comes out of La Tralla. Xammar has made his name and is wielding the pen. The journalist Jaume Pasarrell, a colleague of his early days of journalism, saw it at once: "he was an extremist journalist". Always going beyond the limits. In El Poble Català, the daily that aspired to be the repository of Catalan nationalist republicanism, he began his rise, writing articles with a political and social sting: impetuous, clear, original.

Yet the Barcelona of the Tragic Week of 1909 doesn't fit well with that young man: it is really Xammar's Year Zero. This is when he begins to live in the world. He leaves for Buenos Aires and works in the dailies La Argentina and El Diario and then heads for Paris (from 1910 to 1912) to be a bohemian. In 1913 he's seduced by London. He works as a translator and joins the editorial staff of The Manchester Guardian, and comes to be El Día Gráfico's man "correspondent-ing" with Julio Camba, Ramiro de Maeztu and Salvador de Madariaga. All this as the First World War is breaking out.

And now we have him: special envoy – on the French front and with the British fleet – of La Publicidad and the Iberia agency. Always on the move, he pokes about, rummages around and finds original, vivid, audacious points of interest: a flight in a biplane, over the boats, soldiers behind his knapsack... The journalist knows how to frame reality, then presses the button and the snapshot is sharp, interesting and... it is news.

With the Great War, journalistic ophthalmology gets its focus and Catalonia is mirrored in Europe. The country enters through the triumphal arch of journalism: Xammar, the columns of Agustí Calvet (Gaziel) and all the young men who, like Pla, will come in their wake. They care about the techniques and methods of work in modern professional, rigorous, synthetic, journalism, with data, nuances and rich sources of information, on familiar terms with reality. This model, with a Saxon accent, will be Xammar's disembarking in the Catalan press. In 1918 he returns to Barcelona as editor-in-chief of the pro-allies review Iberia and correspondent for the American newspaper The World. Moreover, the War is to be a source of inspiration for Xammar. He writes a brief, penetrating and, once again, visionary essay (very little known then and now) with a title that says it all: Contra la idea d'imperi [Against the Idea of Empire].

By the time he is thirty, Xammar's life is like a news item: born and expiring every day. From 1919 to 1922 he works in Madrid (El Sol, Fígaro and La Correspondencia de España) and in Geneva as an editor for the League of Nations. He expands his circle of contacts, sources of information, friends, experiences, articles... and again sniffs out the news: now Germany.

Eugeni Xammar's stay in Germany from 1922 to 1936 is the most brilliant stage for the journalist but the most distressing for the person, and he has a foreboding: Europe and Catalonia will crumble. In 1922, Xammar becomes the correspondent for La Veu de Catalunya and, in 1924, for La Publicitat, the two leading Catalan dailies, both of which are comparable with the European press. He portrays, as no one else does, the Germany disabled by war, the country that would incubate Nazism, in L'ou de la serp [The Serpent's Egg] – a work that would bring together some of his columns from Germany in the 1920s: ruined towns and villages, the rebirth of Berlin, and a legendary interview of the future, with Adolf Hitler. He does the interview with Josep Pla and together – the man from Llofriu is, as of 1923, La Publicitat's roving correspondent for Europe – they travel Germany and a good part of Europe (in the book Periodisme [Journalism] there is a collection of articles on this period).

However, in 1931 Xammar looks at Europe and once again sees the "crossroads", the "road of peace" and the "road of disquiet". He looks at Catalonia and comprehends that the Republic is only "a flash that came to light up a sky full of baleful presentiments". Xammar always perceives it all before it happens: with a headline, a phrase. And now he has changed the face of it. As correspondent for the daily Ahora and for a chain of American publications he relates the ascent, triumph and devastation of Nazism like few other journalists: the lunacy of the mass meetings, the boycotting of minorities, the sterilisation campaigns, the spectacular Nazi propaganda apparatus... (this period is collected in the volume Crónicas desde Berlín [Chronicles from Berlin]). Meanwhile, in Catalonia too, his articles run up against problems.

In January 1936, "one of the best Catalan journalists" starts writing for the satirical weekly El be negre under the pseudonym of Peer Gynt. Xammar is hundreds of kilometres away and inveighs against everything: he announces a coup d'état and anarchist social agitation. He receives death threats. Europe and Catalonia have become moribund. The journalist has to flee from the Spanish embassy in Berlin where he is head of press. In Paris, the same embassy and the same job await him. He works with the Generalitat (Catalan Government) in exile and for the American agency Associated Press.

Xammar is a survivor but, more than anything else, he is a professional of tomorrow. In the early fifties he goes to Washington to work as a translator for the United Nations. Some years later, he returns to Europe to engage in similar work for the World Health Organisation in Geneva. Since the days of the disasters he has been working with different Catalan publications produced in exile. His name is already legendary: mythical, faraway and virtual.

In 1973 he died at the age of 85 in the family home at L'Ametlla del Vallès where he had been spending long periods since his retirement in 1971. Xammar has not remained "unpublished", as Josep Pla prophesised, although part of his life, all he saw and described of the world, is yet to have the scent of paper and is still flying in the air (his memoirs are compiled in Seixanta anys d'anar pel món [Sixty Years of Roaming the World] and one can also read the biography Periodisme? Permetin! La vida i els articles d'Eugeni Xammar [Journalism? Just Let Me! The Life and Articles of Eugeni Xammar]), no doubt because, as his friend said on his death, Xammar lived "from the future".

Copyright © Francesc Canosa Farran