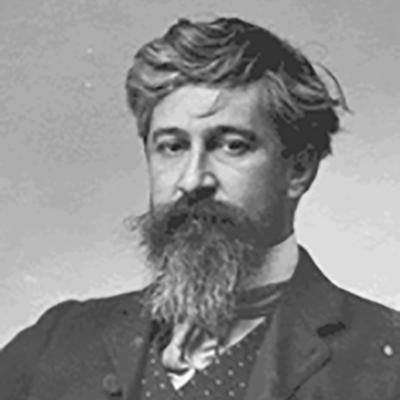

Santiago Rusiñol

Margarida Casacuberta (Universitat de Girona)

When he started to write at the age of twenty, Santiago Rusiñol i Prats (1861-1931) was working in the family business and painting in his spare time. He also enjoyed hiking and had begun to collect pieces of old Catalan ironwork, which he found in farmhouses and hermitages when he was walking in the country with other members of the Associació d'Excursions Catalana (Catalan Ramblers' Association). One of Santiago Rusiñol's first published texts describes one of these excursions.

It was during the year of 1881 that Rusiñol walked the Taga-Sant Joan de les Abadesses-Ripoll route, taking with him pencil, pen and paper. He had been asked to write a detailed account of the excursion for the bulletin published by the Association. The text, illustrated with his own drawings of nature, is in the purest romantic style. His description of the landscape, his reflections on the sense of history and his admiration for the portal, almost in ruins, of the Ripoll monastery are the basic ingredients of the sketches of elegiac, patriotic tone, which he was to repeat in 1883, this time in the different setting of the Centelles castle.

Nonetheless, not everything was romanticism and elegy in these early texts by Rusiñol. Just as his painting was evolving from Olot School-style landscape painting to a taste for sordid spaces, his literature was also moving through a period of naturalist longing. From his own version of naturalism, which was closer to parody than to acceptance of the assumptions of the movement, he expressed this in some truly surprising texts: the letters he sent to the women who was soon to be his wife, Lluïsa Denís. Written in Spanish and addressed to a highly particular and singular reader, Santiago Rusiñol's letters to his fiancée are, first and foremost, pure literature. The essential interest of this literature lies not so much in Rusiñol's ability to follow the conventional codes of the amorously inclined epistolary genre but, on the contrary, in his deliberate use, from an ironic distance, of its each and every cliché, after which he explicitly reveals the code. Systematic hyperbole determines the appellatives by which the "I" addresses his beloved, the bewailing of the forced separation of the lovers, and the impediments –real or invented, it is of no matter– with which the family and society in general try to thwart their happiness. In contrast with this dramatic register, the enamoured writer also uses the space of the letter to describe his adventures and those of his friends in a highly realistic tone that can turn into caricature and thence to verging on black humour and, when very necessary, scatology. These letters to his betrothed are, then, a sort of testing ground for Rusiñol's literature. Perhaps they inadvertently turned into literature but I believe one should not forget that, at the same time as he was writing these letters, Rusiñol and his friends at the Centre d'Aquarel·listes (Watercolourists' Centre) were upholding a modest kind of painting as an alternative artistic space vis-à-vis official, academic painting, and that they took a militant stance by exhibiting sketches, drafts and trial versions. In other words, while his letters were not written to be published, they likewise respond to the need to experiment, through different languages, with new ways of understanding the relations between reality and fiction.

And this need for experimentation is what marks the first steady steps of Santiago Rusiñol in the terrain of literature, steps that significantly coincide with his decision to make a profession out of his zest for art and to take on the mantle of the modern artist with all the consequences involved which, in the long run, meant forging a work of art out of his own existence. The first signs of this process can be situated between 1887 and 1888 and coincide with the death of his grandfather, patriarch of the family, with the separation from his wife and with the painter's move to Paris. All these facts pertaining to the private life of Santiago Rusiñol are automatically integrated into the story that explains and justifies the conduct of the personality. This narrative, in fragmentary form, appears published in the pages of La Vanguardia, Catalonia's most up-to-date newspaper at the time. It is not a conventionally autobiographical account. The "I" does not appear as the main character but as a point of view, a gaze that selects and interprets reality and that belongs, this yes, to an extremely sensitive, extremely lucid and extremely critical individual. This is the gaze of the Artist –with a capital A– the same gaze that unifies the letters to the editor that, once installed in Paris, Rusiñol sent from Montmartre to La Vanguardia under the general heading of Cartas desde el Molino (Letters from the Windmill – 1890-1892). With the Moulin de la Galette as his leitmotif, Rusiñol becomes the chronicler of bohemian life, of the sacrifices of its practitioners and of the awesome power of the artistic ideal. All of this transpires through the ironic distance, the bittersweet flavour, the touch of ambiguity and the unpretentious tone that characterise Rusiñol's literature at this time.

Staying true to the artistic ideal involves a lot of risks, even death. Renouncing it leads inexorably to failure and personal annihilation, which is another form of death. Rusiñol decided to accept the risks and to take the vows of the priesthood of art. He therefore embarked on the project of constructing in Sitges a house-cum-workshop which, more than a house, was a temple and he publicly adopted the image of a dandy. He also continued, accordingly, to send his pieces to the editor of La Vanguardia together with his literary chronicles –Desde una isla (From an Island, 1893), Desde otra isla (From Another Island, 1894) and Desde Andalucía (From Andalusia, 1895), writings that were finally brought together and published with the title Impresiones de arte (Impressions of Art, 1897)– offering his particular vision of the world, which is that of the Artist that he had set about incarnating. However, he then immediately also went on to consider the possibility of engaging in literary creation apart from journalism and would thus become, with the publication in L'Avenç of "La suggestió del paisatge" (The Suggestion of Landscape) and "Els caminants de la terra" (Wayfarers of the Earth), the man who introduced the prose poem into Catalonia and Spain.

That Santiago Rusiñol was enthusiastic about this new genre is demonstrated with the translations he did for L'Avenç of Baudelaire's prose poems and, in particular, the mark made by these poems in Rusiñol's first books Anant pel món (Wandering in the World, 1896), Oracions (Orations, 1897) and Fulls de la vida (Pages of Life, 1898), three examples of a very new kind of literature linked with French symbolism and decadentism, blurring the borders between genres and incorporating itself into a new concept of art: Total Art. The graphic arts, music, painting and literature –fiction, poetry and theatre– come together in the creation of refined products which the author dedicates, in each of his prologues, to a select minority of people who were able to appreciate their real value.

This elitist discourse, true to the image of the dandy artist cultivated by Rusiñol, is the same as that which one finds in the milieu of the Modernist Festivals of Sitges (1892-1897), which were organised under the auspices of the modernist movement as an alternative to the stagnation and provincialism of turn-of-the-century Catalan culture. Rusiñol who, from the very start, had agreed to lend his image to the movement, was the promoter of an exhibition of paintings (1892) and of the premiere of the play The Intruder (1893) by the emblem of Belgian symbolism Maurice Maeterlinck, while he also the prime mover of a modernist literary competition (1894) and the premiere of La fada (The Fairy, 1897), the Catalan opera by Enric Morera and Jaume Massó i Torrents. The elitism of these aesthetic approaches was soon transcended by a regenerationist reading occurring within the Catalan nationalist circles that were then starting to organise politically. Or by a reassessment of these initial proposals by Rusiñol himself. In L'alegria que passa (Passing Happiness, 1898), the first long piece he wrote for the stage as part of a campaign to introduce the genre of Catalan lyric theatre, Rusiñol achieves an almost perfect symbiosis between symbolism and folk theatre, between tradition and modernity, all of which led to its being a great success with critics and public alike, at a time when renewal of Catalan theatre was deemed to be a patriotic imperative. In this work Rusiñol presents the eternal conflict between the artist and society, poetry and prose, spiritualism and materialism by way of highly symbolic stage sets and characters. He takes up the same theme again in El jardí abandonat (The Abandoned Garden, 1900), his most genuinely symbolist work and also in Cigales i formigues (Grasshoppers and Ants, 1901), in which didactic intention and burlesque humour end up bursting out from within the symbolist code.

Santiago Rusiñol's entree into the world of theatre coincided with a delicate moment in his life, which was threatened by serious health problems that led to his undergoing a cure for morphine addiction and the removal of one of his kidneys. By this time it had been noted that, with the recovery of his health, Rusiñol had introduced a major change into his pictorial and literary work. With his specialisation in painting gardens, on the one hand, and his almost total focus on drama, on the other, his work soon manifested the effects of repeated formulas and clichés that assured him a favourable response from the public. Works such as Llibertat! (Freedom! 1901), El malalt crònic (The Chronic Invalid, 1902), Els Jocs Florals de Canprosa (The Prosehouse Literary Competition, 1902), L'hèroe (The Hero, 1903), El pati blau (The Blue Courtyard, 1903) and El místic (The Mystic, 1903) resorted to gambits such as polemics, denunciation, folklore and sentimentalism in order to pull in bigger audiences, the ultimate objective of an author who saw direct contact between writer, oeuvre and public as the only way of ensuring an enduring, standardised Catalan literature. Hence, in a prologue that Rusiñol wrote for the work Llibre del dolor (Book of Pain, 1903) by Jacint Capella, after having upheld freedom of theme and aesthetic treatment, and championed, above all, sincerity and spontaneity, he expressed the need to enter into direct contact with the public which, after all, was the main target of any work of art. "In art, as in so many other matters, what gives out most beauty is what gains most devotees; and the man who sheds most brightness is the one who attracts most moths." Rusiñol thus formally breaks his ties with modernism and puts into words what, since the turn of the century had been perceived as an incontrovertible fact: Santiago Rusiñol had gone from being a modernist to a modish author.

The first and toughest reflections on the option taken by Rusiñol appeared in the pages of the review Catalunya, of which Josep Carner was then director. The criticism only grew harsher when the artist, in his facet of the prose writer, had been presented as one of the possible exemplars for the creation of a modern literary language. The people of Catalonia had been convinced –thanks to its basic Barcelona perspective and tongue-in-cheek treatment of reality– by the work El poble gris (The Grey People, 1902), a collection of stories that prefigures, on the basis of the unifying gaze of a narrator, the symbolic novel that emerged from the crisis of realism. What unsettled them, however, was his defence of the model of an artist –messianic, critical, uncompromising– who was light years away from that subscribed to by those who were immersed in the process of a selective modernism that would eventually lead to the articulation of the anti-modernist cultural movement of noucentisme. Modernism was the model that Rusiñol continued to incarnate and for which, in El místic, the controversial figure of Jacint Verdaguer, victim of society's incomprehension and hypocrisy, was the reference. After El místic, Rusiñol embarked on the one-way road of making concessions to the wider public –with Els punxasàrries (The Tax Collectors, 1904), El bombero (The Fireman, 1904), L'escudellòmetro (The Soupometer, 1905), La nit de l'amor (Night of Love, 1905), La lletja (The Ugly Woman, 1905), El bon policia (The Good Policeman, 1905)– and, moreover, he does this pragmatically. In other words, he was upholding a model of alternative culture, over which the young professionals in the sphere were striving to prevail. After 1905, since, according to Rusiñol, this alternative meant taking the path of popularity, a strengthening of ties with the public, he entered the world of the publisher Antoni López. From the very core of artisan culture, Santiago Rusiñol fended off the assaults of the young noucentistes, for whom he was one of the main offenders. He had become the emblem of badly written, mindless and slapdash work, and what most incensed these young people was the fact that Rusiñol remained firm in his hubris and independence of the modernist artist.

On 21 June 1907, Santiago Rusiñol availed himself of the pseudonym "Xarau" for the first time and he was to continue using it in the pages of the review L'Esquella de la Torratxa until 1925 as he waged his battle against the Catalan culturalist discourse of noucentisme. From Llibreria Espanyola, the publishing house of Antoni López, he continued to publish his dramas, comedies, one-act farces and vaudeville pieces, together with three novels El català de «La Mancha» (The Catalan of "La Mancha", 1914), La «Niña Gorda» (The "Fat Girl", 1917) and En Josepet de Sant Celoni (Little Joe from Sant Celoni, 1918), more arrows in his anti-noucentista quiver. Over all these years, Xarau continued his parodying of the Glosari of Xènius while exalting the lost paradise of his youth and evoking personalities and landscapes of nineteenth-century Catalonia.

This is certainly an abysmal gap. Perhaps it is as abysmal as that lying between the publication of the novel L'auca del senyor Esteve (The Tale of Mr Esteve, 1907) and the stage version of the work, which was premiered in 1917. Between these two poles, the figure of senyor Esteve, emblem of the bourgeois gentleman and antithesis of the artist in the eternal struggle between poetry and prose that runs through all of Rusiñol's literary work from start to finish, takes on significantly more endearing features and comes to win the heart of the spectator who automatically identifies with the character in the framework of the skilled worker's Barcelona idealised by comedy. If Barcelona is what it is, this is thanks to senyor Esteve. If the artist has finally found his place in society, it is senyor Esteve with all his sacrifices who has made this possible. In view of this evolution it is not surprising, then, that in an interview of 1924 Santiago Rusiñol incorporated senyor Esteve into his own biography for the first time and that, thenceforth, the two myths walked the path of posterity together.

Copyright © 1999 Ediuoc/ECSA